In 1886, Karl Benz patented the first petrol-powered automobile. It was the first step in the evolution of transportation; a milestone with world-altering consequences. Today automotive companies are among the most influential businesses on earth. Their branding represents entire nation’s pride, their stereotypes, and has cultivated an international following of fans and personal business ventures like no other industry has. However measurable the impact of Karl’s creation could be, it can ultimately be checked in balance by the contributions of one man who proverbially shifted the industry into what it has become today. That man is Harley J. Earl.

A time span of forty years separates Karl’s patent and the inception of Earl to General Motors. It was there, at GM, that he would foster the ideas, designs, and techniques that automakers utilize nowadays. Before he was brought into GM in 1927, though, he honed his skills and sculpted a career for himself in the city most known for its love of the automobile: Los Angeles, California. However, to properly set up the story to reflect his impact requires consideration to be given to how things were in the automotive era predating his start at GM.

In those early years, after the birth of the car, there was essentially no concept of automotive design beyond pure engineering. Mechanical engineers introduced improvements on vehicles as they deemed fit and the styling of mass-produced vehicles was relatively ubiquitous among makers. Only affluent buyers were able to afford tailormade cars that possessed unique styling and exotic engineering. It was at his family-owned carriage workshop in Los Angeles building personalized cars for Hollywood movie stars that Earl would first begin to sharpen the valuable styling skills prized by GM.

In 1927, Cadillac recognized Earl’s ability and hired him as a consultant for the construction of their LaSalle. Twenty-seven thousand sold units later, Cadillac was utterly amazed by the unprecedented response they had received to their new car. Alfred Sloan, President of General Motors, immediately extended an offer to Earl to become the head of the first design studios – he accepted. This was not only a first for GM but also the first design studio of any major automotive manufacturer in the world.

Earl approached this new task with a simple, yet grand, mission, which was to make custom coachbuilt styling available to the masses. Only a few years after establishing the GM Art & Color Section it was granted membership into GM’s administration board. By 1940, Earl was heading up design as the Vice President of Styling, and ten years later his exclusive group of artists was abreast in power to the Engineering and Financial branches of GM. General Motors, in less than thirty years, had propagated themselves into a powerhouse of innovation with the hiring of a single man.

Critical to the success of General Motors was Earl’s idea of the concept car; an idea that originated in 1938 with his Buick Y-Job. Before then the idea of making a vehicle purely to gauge the reactions of audiences had been relatively unheard of. The Y-Job was essentially no more than a lustfully low and wide market research project that proved Earl’s penchant for designing what the people wanted to purchase. His acumen for such desires is evident throughout his career at GM, which is marked with yearly concept cars that pushed new and radical designs to the forefront of GM’s publicity.

Earl toured the United States with these concept cars, using them as promotional tools and promises of things-to-come. By the 1950s cities all over America were petitioning General Motors to hold one of their Autorama events in their towns. Crowds of consumers flocked to displays, captivated by the space-age styles. All were hoping to get an early glimpse of next year’s model improvements or future designs. Although most concept cars never fully materialize into production vehicles, it was through these design studies that Earl’s idea of “dynamic obsolescence” appeared.

The notion of “dynamic obsolescence” being that each year a series of small modifications were introduced to vehicles that would keep consumers desiring the newest, most current models. These design changes could be as simple as interior color options or as significant as major exterior styling alterations. Earl not only had a strong proclivity for styling design but also engineering improvements. He and his team, numbering in the thousands by 1950, supervised the introduction of permutations to the car like distinctive grill designs, chrome windows, driver-focused instruments, streamline bodies and bumpers, hidden spare tires, incorporated trunks, heated seats, car radios, and many more.

All of these improvements stemmed from his philosophy that “a picture is worth a thousand words and a model is worth a thousand pictures.” During his tenure at GM, Earl popularized the now commonplace practice of using full-sized drawings and clay models. His skilled talent and paradigm-shattering thinking permeated in his team, and other manufacturers were so envious of GM’s prosperity that they would actively attempt to purloin members of Earl’s team. Nevertheless, Earl was not selfish with his visions of the future and greatly furthered the prospect of design studies by founding the prestigious Art Center College in his home city in 1934 – a move that proved exceedingly beneficial to General Motors for prospective hiring.

Being as perceptive as he was, Earl was quick to recognize the talents outside of his gender. In 1943, he was responsible for hiring the first female automotive designer. A practice that he would continue throughout his leadership of the General Motor’s Styling Department. Not averse to the controversy he also pulled into his ranks openly-gay designers; an extremely contentious decision during the forties and fifties.

As with any revolutionary, there are detractors, and Earl’s alternative judgments lead to significant envy and resentment among the male-dominated industry – not even just for his hirings. Earl was a humble man in the perspective of his celebrity status, admonishing those that solely attributed his design team’s work to himself. Although, the celebrity status was certainly warranted.

At the forefront of unveilings and appearances, he was always in the spotlight. He hosted lavish dinner affairs for his employees and members of the press on GM’s expense. He was also seldom seen driving a car that was not a one-off; often having rare vehicles flown to locations solely for his use!. Nevertheless, GM’s executives were not blind to where their success emanated from and gratefully allowed his expenditures because of his continuous achievements. Of all his achievements though one certainly stands above the rest, and that is his design and direction for the birth of America’s first sports car: the Corvette.

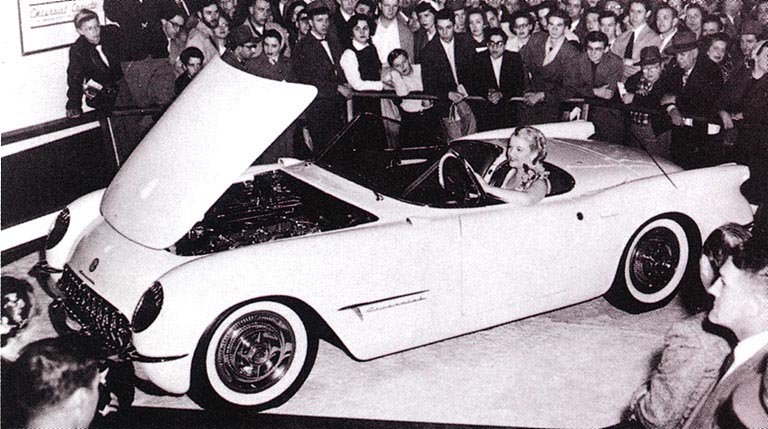

During 1951, the Styling Department released the Le Sabre concept car during a race at Watkins Glen Raceway in New York state. Earl noticed not only the crowd’s enthusiasm toward the performance of European sports cars, like that of Ferrari but also the design language they had. He quickly recognized that America had no real rival of such cars and set to work. Two years later, at the same event, he introduced to a star-struck crowd the Corvette, and the world has reeled ever since.

Five years later, in 1958, Earl retired from his post at General Motors. After his retirement, the position he left was too large for any one person to fill adequately. Other departments swiftly moved to secure any power they could over the vulnerable department, ushering in the beginning of the end for GM’s styling spearhead.

Regardless, Earl’s legacy lives on with unfortunate obscurity. For the man that gifted the world so many innovations that it birthed national car rivalries and a shared international passion for the automobile, he does not receive nearly as much credit as many others that followed him do. Ultimately, as the car fanatics that we have become, we owe you immeasurable thanks, Mr. Harley.